“One can say that Javert is our conscience. The ever lurking presence of the law and our own condemnation. The tension between who we were and who we are and who we can be. Javert represents that inescapable, shameful past that forever haunts and pursues one’s conscience. Javert is the man of the law, and… There are no surprises with the law. The principle of retribution is simple and monotonous, like Euclidean logic. It’s closed to all alternatives and shut up against divine or human intervention… Indeed, Javert represents the merciless application of the law, the blind Justice that in the end is befuddled by hope and the possibility of redemption without punishment.”

― Cristiane Serruya, Trust: Betrayed –

The stage production of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables is my all-time favourite musical. Les Mis lovers will debate for hours about who is their most beloved character, or which actor is the most believable as Jean Valjean, or which production and performance rivals no other. Mine is the 25th Anniversary concert performance at the O2 in London, with the incredible talent and voice of Alfie Boe as Jean Valjean, Lea Salonga as the tragic persona of Fantine, Samantha Barks as Eponine, and Norm Lewis as Javert.

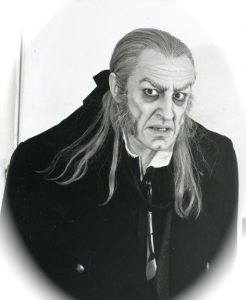

What is it about the character of Inspector Javert that draws us in and simultaneously repels us? I hold a mixture of profound pity, intense anger and utter frustration as I observe his complete obsession in meticulously enforcing what he believes to be the right way, the law, the moral order of society. Javert is a slave to the law. The law that he never questions, the law that he uses as a lens through which to see the world, the law that dictates to him whether a person is good or evil. He clutches to the law that becomes his saviour as he tries to escape his felt shame from a past story – that of being the son of a fortune teller and a galley slave. The law that provided a legitimate covering for the hate and disdain he feels for people like Valjean. Ultimately, it is a hatred he feels for himself.

He is a man who allows himself little pleasure and adheres to the strict moral code he enforces on others. Everyone who meets him is afraid of him. His character is ruthless and confident as the general in his black and white world. There is no room for kindness or mercy – either to others or to himself. In fact, the book makes it very clear how he is quite convinced he is not worthy of any good thing in life … he sees himself as worthless.

Javert is such an interesting character because he reminds us of something … of someone … Javert reminds me of a part of my conscience that is like a bloodhound – never letting up. The inner critic doubting myself and questioning my motives. Those who are also Ones on the Enneagram will probably recognise and appreciate this metaphor of Javert and the journey to learn to let him go.

I also recognise Javert in the ideas about faith and religion that I clung to in the first half of life. I have found this so illuminating. A child looking for security in a world in flux would be drawn to a fundamentalist, conservative belief system – a religious expression that favours those who believe ‘right’, act ‘right’, speak ‘right’ – a religious world that prides itself in absolutes and having all the answers. Like the law became the saviour for Javert, this moralistic belief system becomes the saviour of so many, who like myself, were drawn to the idea of perfectionism and certainty. We even had a book that could be weaponised according to our cultural interpretation and understanding to determine who was doing life ‘right’ and who wasn’t. And those who weren’t needed to be’ saved’, and those who were ‘saved’ and still not doing it ‘right’ were ‘backslidden’, ‘heretics’, or ‘rebellious’. Of course, we did it all in the name of ‘love’. ‘We love the sinner but hate the sin’ or ‘We welcome you, but don’t affirm you’ is some of the bollocks we told ourselves … and, unfortunately, others …

When Javert is our taskmaster, disguised as the voice of conscience or religious idealism, we become tired. Because Javert is insatiable. Ultimately, Javert is driven by a sense of feeling unworthy. This can lead to self-destructive habits or religious pietism that deflect the sense of shame on to others who are not doing it ‘right’. We can live our whole lives like that – hounded by Javert. Or we can let him go.

So how do we let go this dominant voice from around our dinner table of life? Perhaps we start by inviting another character to our table – one who also understood shame and suffering, but instead of the law, he encountered grace and grace became his guide to life. He stumbled on this grace through the loving actions of a priest – Bishop Myriel – whose whole philosophy of life was summed up by Hugo as: ‘There are men who toil at extracting gold; he toiled at the extraction of pity. Universal misery was his mine. The sadness which reigned everywhere was but an excuse for unfailing kindness. Love each other; he declared this to be complete, desired nothing further, and that was the whole of his doctrine.’ Bishop Myriel was healing ointment on Valjean’s scars at the hands of the law.

Valjean modelled the grace he experienced. His life tortured Javert. Why? Because Valjean gave Javert irrefutable evidence that a person is not necessarily evil simply because the ‘law’ says so. Javert could not reconcile this – this scandal, this grace. Grace silenced Javert.

‘I am reaching, but I fall, and the stars are black and cold, as I stare into the void, of a world that cannot hold. I’ll escape now from that world; from the world of Jean Valjean. There is nowhere I can turn. There is no way to go on!’ (Javert)

Letting go of the black and white world of Javert is not as easy as it sounds. Javert is often deeply embedded in our sense of self. We need a guide. We need Jean Valjean to show us this pathway of grace and love. For love is greater than the law, it always has been … sometimes we can forget this.

‘Take my hand and lead me to salvation. Take my love, for love is everlasting. And remember the truth that once was spoken – to love another person is to see the face of God.’ (Valjean)